AI Agents in Business: A Leadership Perspective

In many leadership conversations today, AI agents come up quickly.

Almost every organization says they are already using them.

What they usually describe, though, is not an agent.

It is automation with a conversational layer.

This confusion is easy to miss, and expensive to ignore.

Because when leaders misunderstand what an AI agent actually is, they assign it the wrong expectations, the wrong controls, and the wrong ownership.

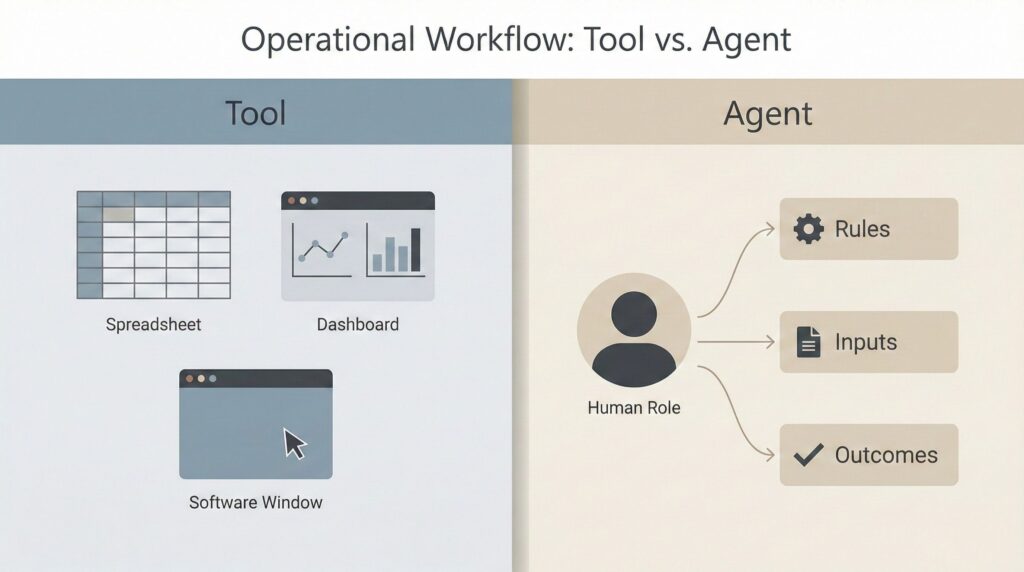

Tools and agents are not the same thing

A simple distinction helps.

A tool is something you use.

An agent is something you manage.

Excel is a tool.

So is a CRM, a dashboard, or a script that runs on demand.

You decide when to open it.

You decide what question to ask.

You decide what to do with the result.

An AI agent behaves differently.

Once set up, it does not wait to be clicked.

It operates within a defined space.

It observes inputs, applies rules, and produces outcomes.

A familiar office analogy works well here.

Tools sit on desks.

Agents sit on the org chart.

That one shift changes everything.

Why this distinction matters for leaders

Most problems with AI agents are not technical.

They are managerial.

When something is treated like a tool, no one feels responsible for its decisions.

When something is treated like a role, responsibility becomes unavoidable.

In organizations where agents are deployed casually, the same questions surface later, often after something breaks.

Who decided what the agent is allowed to do?

Who reviews its output?

Who steps in when the result is wrong, incomplete, or inappropriate?

Without clear answers, risk quietly accumulates.

Not because the system is malicious.

But because no one is clearly accountable.

The real gap in most organizations is AI agent ownership, where responsibility is assumed but never clearly assigned.

A common operational example

In one operations setup I’ve seen more than once, an AI agent was introduced to triage incoming requests.

Initially, it worked well.

Response times improved.

Teams trusted the outputs.

Over time, the agent began making small judgment calls.

Nothing dramatic.

Just prioritization decisions that humans used to make.

When an issue finally surfaced, leadership asked a simple question.

“Why did the agent do this?”

No one had a clear answer.

IT assumed the business owned it.

The business assumed IT was monitoring it.

Everyone assumed someone else had defined the boundaries.

The agent did exactly what it was allowed to do.

The problem was that no one had explicitly decided what that should be.

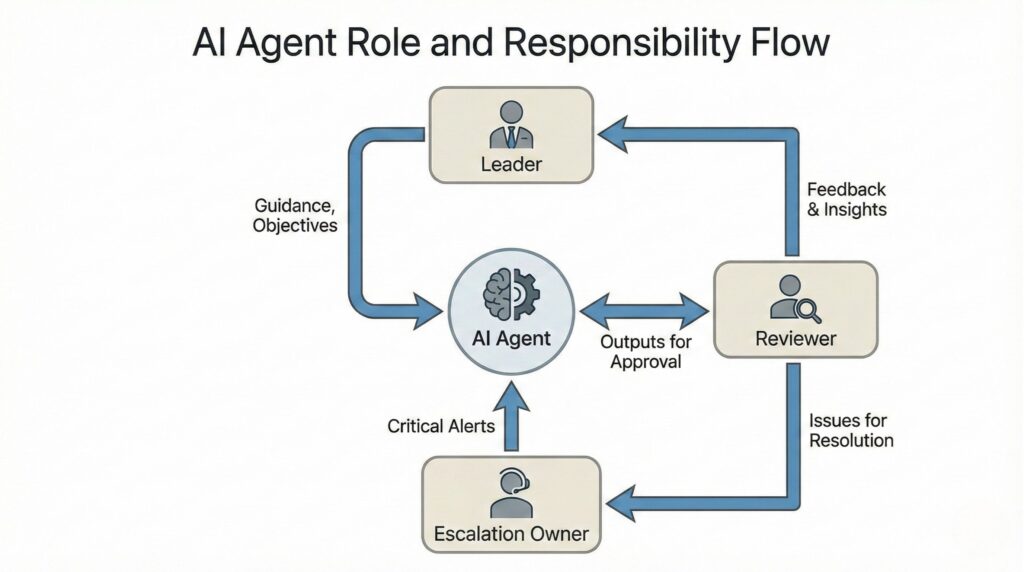

Managing AI Agents Requires the Same Discipline as Managing People

Once an agent is operating independently, leadership discipline matters.

Clear scope.

Regular review.

Defined escalation.

This is why managing AI agents looks far more like people management than software management.

Without that mindset, accountability stays blurred.

A pattern I see repeatedly

The pattern is consistent across functions.

An agent is introduced to improve efficiency.

Early results look promising.

Volume increases.

Edge cases appear.

Then something feels off.

Outputs drift slightly from expectations.

Decisions are made that no one explicitly approved.

Exceptions are handled inconsistently.

When leaders investigate, they discover something simple.

There was no owner.

Only operators.

Everyone assumed someone else was watching.

The most common mistakes leaders make with AI agents

The same mistakes show up across industries.

The first is treating agents as features.

They are approved during implementation, then forgotten.

The second is confusing access with authority.

Just because an agent can see information does not mean it should act on it.

The third is assuming review will “just happen.”

Without an explicit owner, review becomes occasional and informal.

None of these are technical failures.

They are leadership blind spots.

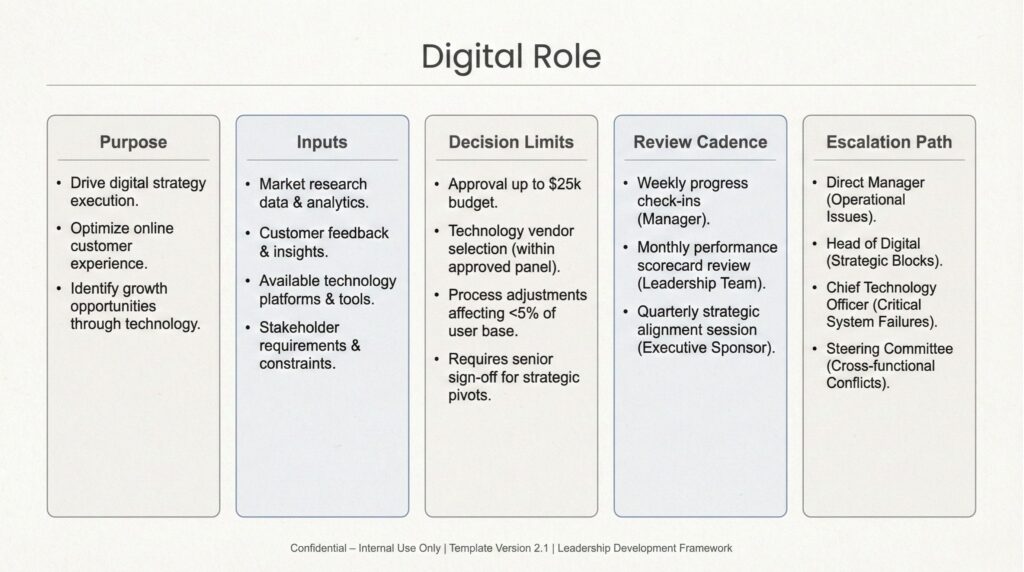

Reframing AI agents as digital roles

The organizations that handle this well do something subtle but important.

They stop thinking about agents as software.

They start thinking about them as digital roles.

Not employees.

Not replacements.

Roles.

Each role has a purpose.

Each role has boundaries.

Each role is reviewed.

When leaders frame agents this way, the conversations improve immediately.

What is this role responsible for?

What information can it access?

What decisions can it make on its own?

When must it escalate?

How often is its work reviewed?

These are not new questions.

They are the same questions good leaders ask about people.

Over time, AI agents will sit alongside humans as digital workforce roles within the organization.

An example from people functions

In people operations, agents are often used to screen, schedule, or respond.

In one scenario, an agent handled early candidate interactions.

It followed policy.

It stayed within the system.

What no one noticed at first was tone drift.

The responses were technically correct, but subtly misaligned with the organization’s culture.

There was no failure.

Just a gradual erosion of trust.

Once a single leader was made responsible for reviewing the agent weekly, the issue disappeared.

Not because the technology changed.

Because ownership did.

AI Governance Leadership Is About Accountability, Not Control

Governance in this context is often misunderstood.

It is not about restricting systems or slowing teams down.

AI governance leadership is about deciding who is responsible, who reviews outcomes, and who intervenes when judgment is required.

When that is clear, speed actually increases.

The leadership implication

This is not a technology discussion.

It is an operating model decision.

Once an agent exists, leadership has already delegated judgment.

The only question is whether that delegation was intentional or accidental.

Strong organizations make it explicit.

Weak ones discover it later.

One practical takeaway for CXOs

Before approving any AI agent initiative, ask for a simple role description.

One page is enough.

Purpose.

Inputs.

Decision limits.

Review cadence.

Escalation path.

If it cannot be explained this clearly, it is not ready to operate independently.

And if it is ready, someone must own it.

A quick leadership check

When reviewing any AI agent, I now ask five questions:

What is this agent responsible for?

What is it explicitly not allowed to decide?

Who reviews its work, and how often?

What triggers human escalation?

Who answers if something goes wrong?

If these answers are unclear, the agent is not ready.

At scale, this becomes a question of enterprise AI responsibility, not experimentation.

A closing thought

The success or failure of AI agents will not depend on how advanced the models are.

It will depend on how clearly leaders define responsibility.

That has always been true for teams.

It is now true for digital ones as well.

I document these patterns and leadership observations at vatsalshah.co.in and shahvatsal.com.

So here is the real question:

In your organization, who actually owns your AI agents today?